Annotating the Literary Panel: Simon Fraser University, 1978

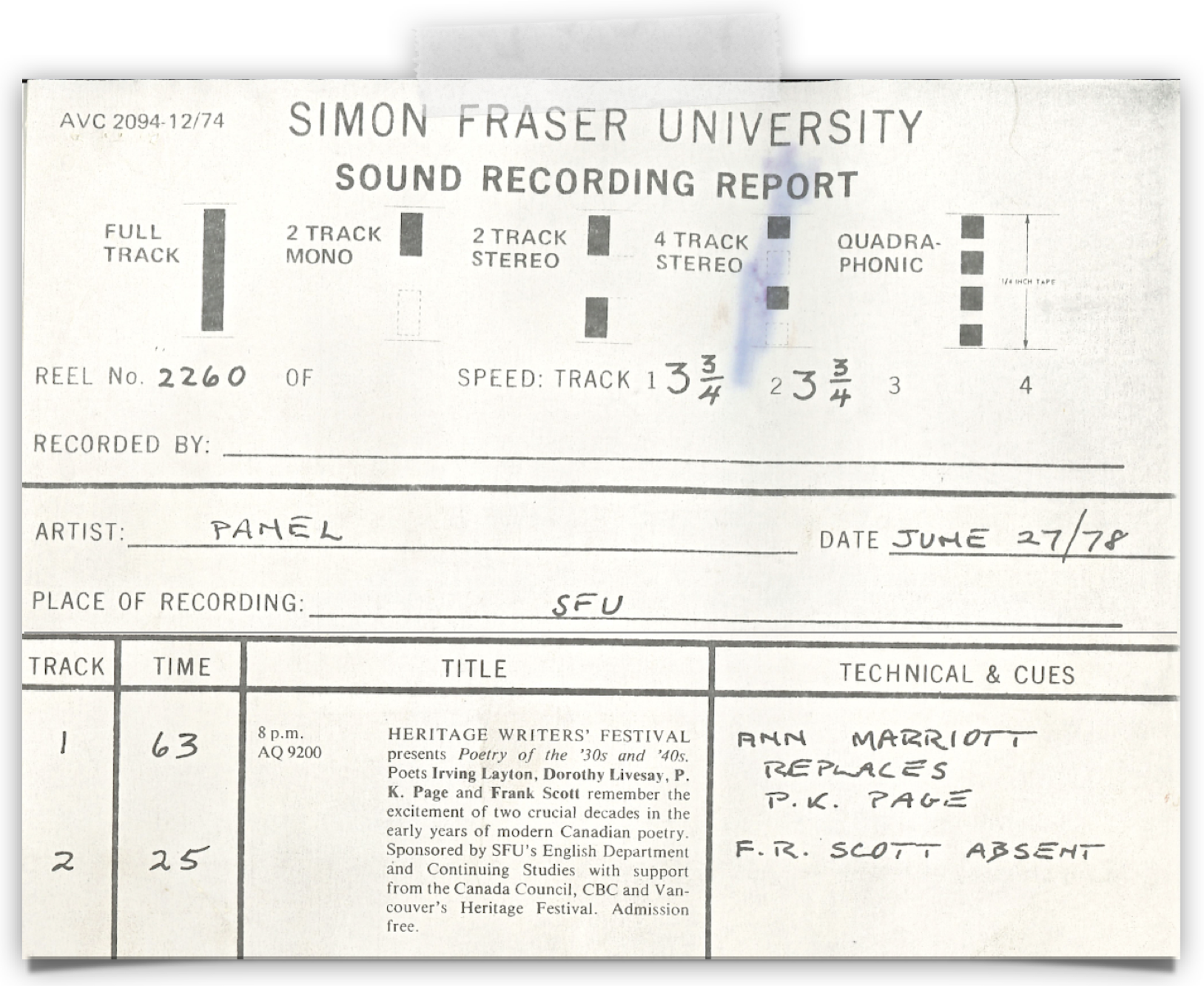

On June 27, 1978, poets Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton were invited to speak at a panel discussion facilitated by Dr. Sandra Djwa and sponsored by the English department and Continuing Studies at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. As part of the Vancouver Heritage Writers’ Festival, a public literary series at the time, their conversation centered on Canadian literary culture and modernist poetry during the 1930s and 1940s. In Livesay’s introductory comments, she addresses what she claims to be the unique conditions of “our time”—specifically, the late 1970s when the event was recorded. As she insists, it is “only” in the time of recording, in 1978, that the defining social struggles of the 20s and 30s were being given appropriate historical attention. The retrospective nature of this historical recording thus reveals the ways in which Livesay, Marriott, and Layton are positioned within the discussion in the late 1970s; they document their participation in the earlier literary culture of the 1930s and 1940s, but also work to re-situate themselves within literary-historical definitions of Canadian modernism and traditionalism. Further, the recording illuminates the materiality of Marriott, Livesay, and Layton’s distinct voices as sources of inter-personal meaning beyond the content of their literary discussion.

In the context of the steadily growing Canadian literary economy in the years after the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957, the panelists’ discussion addresses the earlier significance and new-found prevalence of public readings. Literary reading events, as the panelists note, had become more scarce during the 1930s, but re-emerged as a national phenomenon in the 1960s and 1970s. This emphasis on readings suggests an understanding of the role of cultural activities, including literary panels, through which Canadian literature has been actively defined, critiqued, and re-articulated. While the panelists highlight the broader significance of such events, they also strive to construct, in recorded ‘real time,’ a narrative that resonates with their own listening public of poets and readers in 1978. My annotative approach therefore aims to facilitate an understanding of the recording as a site of negotiation between the three poets. In doing so, it also maps the constellation of the literary communities, cultural institutions, and historical conditions that inform their respective modernisms.

The Canadian Modernists Speak: Framing Modernism

While two other distinguished modernist poets, P. K. Page and F. R. Scott, had originally been invited but were unable to attend the panel, Marriott and Layton were instead asked to speak in their absence. With this acknowledgement, Sandra Djwa, who facilitates the event, proceeds to invoke F. R. Scott “in spirit, since he can’t be here in person” (SFU Archives). Her comment invites listeners to attune themselves to the various ways in which the discussion may have developed—and sounded—differently in the presence and absence of particular voices. It also highlights how the existence and acknowledgement of this unrealized alternative discussion—the one in which Scott and Page are present—informs listeners’ expectations for the discourse to come. Despite Scott’s absence, Djwa positions the poet, both his personhood and the literary legacy that he represents, as a silent authority and interlocutor with whom Livesay, Marriott, and Layton articulate their own positions as modernists. The event’s literary concerns are thus framed within a national perspective as Djwa recites Scott’s satirical 1927 poem titled “The Canadian Authors Meet.” As a gendered, classed, and generational expression of literary politics, this poem has been frequently invoked by critics and poets alike to analyze the cultural divergence between the “traditionalists”—also known as the “Victorian” or “Maple Leaf School”— and the emergent “modernists’’ in Canada during the 1920s (Kelly 54)

Although Scott had been aware of women-identified poets such as Dorothy Livesay, who had been experimenting with modernist forms throughout the 1920s, his poem is a gendered critique of the anti-modernist aesthetic and political tendencies that Scott associates with the Canadian Authors Association (CAA), a literary group composed mostly of middle-class women in the 1920s and 1930s. As Candida Rifkind illustrates in her study of the role of women in Canadian leftist and literary movements throughout the 1930s, the poetic preferences of the CAA membership ranged from lamenting the loss of authenticity brought on by the advent of new technologies, and formally conventional works about “home, hearth, and Empire”— such as those written by one of the group’s most popular poets, Edna Jacques—to the aesthetic and social-modernist experimentation of poets such as Livesay and Marriott (8). The poem’s gendered critique of aging bourgeois femininity also represents the “broader masculinist rhetoric” that was characteristic of Canadian socialism during the Depression (Rifkind 11).

While Scott’s poem not only critiques the traditionalists’ preference for rhyme, metrical forms, and archaic diction, it also draws attention to the values and practices fostered by groups such as the CAA that functioned to overshadow the innovative poetics of some of its members, instead elevating subject matter that adhered to a politically conservative image of Canadian nationalism and “folk” authenticity. In other words, rather than focus its critique on individual poets labouring to replicate traditional forms in isolation, Scott’s satire emphasizes the historical relationship between the elitist social practices of literary communities in Canada and the conservative aesthetics derided by literary modernists who sought alternative routes to engaging poetically with the question of place and nationality.

Mapping Modernist Discourse

Along similar lines, many instances of Livesay, Marriott, and Layton’s discussion in 1978 highlight how these various forces of community networks, cultural institutions, and political discourse—both regional and international—are inseparable from an understanding of their personal trajectories as modernist poets. To address these sprawling nodes and relationships throughout the recording, I decided against using an interpretative approach to generate my annotations out of concern for neglecting valuable references to historical and literary names, dates, events, concepts, publications, venues, and communities. Instead, I retained a word-for-word transcription to serve as a starting point from which to trace how each speaker negotiates between the imperative to convey a documentary account of Canadian literary and cultural history, and the desire to construct a narrative of their personal poetic development. The trajectory of the discussion reflects a dominant understanding of Canadian modernists at the time of the recording; while modernists are valued as socially and politically-engaged cultural producers, they are also tasked with shifting Canadian literary culture from the margins to broader institutional recognition. To varying degrees, this tension between the documentary and subjective/narrative affordances of oral speech therefore provides discursive opportunities for the panelists to align with or resist this framing.

On one hand, Djwa’s introduction positions Livesay, Marriott, and Layton as authoritative players in the poetry “that really laid the foundation, in fact started modern poetry,” and as documentary eye-witnesses of the 1930s and 1940s literary culture in Canada (SFU Archives). Along these lines, Livesay surveys the development of social protest literature across genres and recounts her association with left-leaning literary and activist projects in the context of the Great Depression and the later Spanish Civil War. In doing so, she draws attention to the recent publication of her book Right Hand, Left Hand: A True Life of the Thirties which she claims addresses much of the neglected history of “proletarian” and “labour-oriented” movements in Canada throughout the decade (SFU Archives). As the first speaker, Livesay therefore sets the tone for a thorough and engaged discussion about the political and social issues that defined the 1930s as she assigns significance to the event as an occasion to recuperate the numerous “unsung” voices from a nationally neglected historical archive (SFU Archives). Using the event as a platform to relay her principaled commitments to a receptive audience, she emphasizes the continued relevance and necessity of carrying forward a politically and socially-oriented conception of Canadian modernism, which will in turn help guide the development of literary movements in the 1970s and beyond.

Layton’s overview of the famed rivalry between Montreal little magazines Preview (1942-5) and First Statement (1942-5) also re-articulates a vision of poets struggling to define Canadian modernism through a shared commitment to representing social reality—particularly in opposition to a poetics that catered to the national and traditionalist concerns of conservative academics and the cultural elite. Highlighting the Montreal literary scene as one of the primary locuses for this literary shift, Layton’s historical overview emphasizes how little magazine culture emerged in the 1940s to address the disconnect between the colonial-leaning politics of academic curricula, which elevated canonical British poets, and the wave of modernist literary movements that were taking place in Canada, the United States and Europe. As Layton distinguishes between the Preview group—the “older writers”—whose membership included F. R. Scott, A. M. Klein and later P. K. Page, he compares their cosmopolitanist vision for modernist literary culture and their interest in the English writers such as W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot with the aesthetic preferences of the First Statement group. As Layton recalls, First Statement, the magazine which Layton himself had been affiliated along with poets Louis Dudek and John Sutherland, emphasized the need to “describe the world as we saw it” and to establish a Canadian literature that could define itself independently from the influence of other cultures, particularly England, and instead drew inspiration from the American poets such as E. E. Cummings, Robert Frost, Hart Crane, and Walt Whitman.

In this segment, Layton claims a considerable amount of narrative authority on the subject, given his position as the only panelist who discusses the Preview and First Statement period in Montreal in notable depth. However, by drawing our attention to the negative space of Layton’s voice—specifically the absence of Scott and Page’s voices—this implied authority can be called into question, as alternative possible discourse pathways emerge with the recognition of the event’s contingency. Although Layton addresses the magazines’ shared vision of breaking away from the traditionalist and nationalistic tendencies that had so far characterized mainstream Canadian literary culture, it is likely that a recorded oral narrative from either Page or Scott would produce a different discursive shape, in which the two poets would be provided the opportunity to challenge, elaborate upon, or reframe Layton’s characterizations of Preview’s relative conservatism as well as his depiction of the presumed rivalry between the two magazines.

As a sonic text, the distinct character and oratory style of Marriott, Livesay, and Layton’s voices thus unveils these various inter-relational dynamics that exceed the mere content of their speech. In an attempt to preserve these nuanced layers, my annotative approach aims to capture the rich textual content of these distinct modernist histories, as well as provide a means of mapping the sonic materiality of the various emotional and affective shifts throughout their discussion. For instance, despite Layton and Livesay’s expression of shared leftist values during each of their prepared monologues, the sounds associated with the Layton’s bombastic jokes and interjections—the palpable distortion as Layton’s voice overpowers the microphone and the resulting unsettled audience laughter—present themselves as potential disruptions of Livesay and Djwa’s efforts to sustain a comparatively more measured and objective tone over the course of the event. In such moments, the sounds of laughter, gasps, whispers, and groans from audience members also function to dislodge the illusion of an audience made up of passive listeners, revealing them to be active agents who also play a significant role in shaping the meanings that constitute Canadian literary discourse. In this particular example, the sounds of the audience’s ambivalent reactions to Layton’s gendered comments further reveals the extent to which Layton re-assumes, in 1978, a role not altogether dissimilar to the one he constructs during his retrospective narrative—the modernist poet as social agitator, railing against a stifling and prudish academic establishment. Although Livesay also shares a vision of Canadian modernists as radical agents of change, the absence of these mixed audience responses during her speaking parts is perhaps more suggestive of her capacity to connect to and resonate with the new wave of feminist and ecological movements in the 1970s.

While dividing up my annotation’s layers by individual speaker, audience, and dialogue, I began to speculate that Marriott’s less explicitly political stance—in contrast to Layton’s and Livesay’s self-assured and opinionated rhetorical style—may have been a factor in her contributing significantly less speaking time over the course of the recording. In contrast to Djwa’s positioning of the panelists as literary and sociopolitical authorities, Marriott admits that “listening to Dorothy makes me feel as if I had done nothing in the ‘30s and knew absolutely nothing about what was going on in the Canadian literary scene” (SFU Archives). Her comment draws attention to the implied expectations that each panelist should impart to their listening audience a particular kind of culturally authoritative knowledge. In this way, her statement provides a counterpoint to Livesay’s expansive documentary account cataloguing the major political and social upheavals and literary movements of the 1920s and 1930s. Marriott’s narrative instead recounts the perspective of a shy, sheltered poet, whose encounters with experimental and non-traditional poetic forms are facilitated by a network of family members, new friends, and fellow poets on the West Coast, culminating in her later involvement with Livesay on the Vancouver-based little magazine Contemporary Verse (1941-52). Further, despite Marriott’s deviations from Layton and Livesay’s positions as vanguard poets, her self-conscious and somewhat elliptical oral style provides a refreshing alternative image of herself as a tentative, sensitive, yet also sharply curious observer of the effects of the Great Depression. As illustrated in this example, my annotation layers point beyond an understanding of the panel as a unified discursive object in and of itself by providing listeners the space to zoom into distinct entities—individual panelists, audience members, and moments of unprompted dialogue (or unscripted speech)—to consider how they relate to one another within a larger discursive frame.

While the perceived divisions between the Montreal and West Coast little magazines were arguably less pronounced than the larger rift between the emergent modernists and the traditionalists in the 1920s, listening and annotating recorded dialogue between these representative figures of modern poetry—Layton from First Statement, and Marriott and Livesay from Contemporary Verse— provides the opportunity to reflect upon their competing philosophies and mutual ideals for developing a thriving, passionate, and engaged Canadian literary culture. In analyzing the panel sonically, we are also invited as listeners to entertain a subtler analysis of the rhetorical strategies by which socially-engaged poets such as Livesay, Marriott, and Layton create literary history anew, as they reflexively construct and deconstruct, as well as mythologize and document, a Canadian modernist literary history. These poets sustain its resonance among readers and listeners into the future: our present and beyond it.

Works Cited

Kelly, Peggy. “Politics, Gender, and New Provinces: Dorothy Livesay and FR Scott.” Canadian Poetry, vol. 53, 2003, pp. 54–65.

Rifkind, Candida. Comrades and Critics: Women, Literature and the Left in 1930s Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Simon Fraser University Archives. Simon Fraser University Sound Recordings Collection. F231-1-2-0-0-26. “Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page and Ann Marriott: Poetry of the 30s and 40s,” (sound recording). 27 June 1978.